Bush Video was a collective of artists working in various experimental forms but with video as their main focal point. It was established by Joseph El Khouri and Mick Glasheen during the lead up to the 1973 Aquarius Festival to be held at Nimbin in northern NSW in May that year. El Khouri and Glasheen were invited, along with a number of other experimental film-makers and media activists from Australian universities, to meet with the organisers of the Festival, Johnny Allen and Graeme Dunstan, and decide how they might establish a video co-op to provide a day-to-day video news service and to document the festival. That video should be used rather than film was based on its potential accessibility and cheapness as compared with film, and notions of community video production that had come out of the Canadian Challenge for Change project, in which members of the community were shown how to use media equipment and then made productions that explored issues that were arising out of relations between small communities and the various levels of government.

While Allen was in Melbourne for a pre-Festival Australian Union of Students (AUS) Council meeting in February 1973. David Weston, a Canadian media activist, had given him a paper on the potential use of video in the community, which was then published in a broadsheet that covered the process of getting the festival started. He suggested that

“it will be necessary for the participants to make their own television. It should not simply be a one-way affair, reminiscent of the one-way autocracy of broadcast television. It should be a first step in the democratisation of television giving the means of production and exhibition to anyone with something to say.”1

To make the video equipment available to the Festival participants they proposed that they set up an access centre in the Nimbin township - in a variation of the model that Albie Thoms and Glasheen had based on the British TVX group and established for The Odyssey, a rock festival held at Wallacia, NSW, over the January long weekend of 1971.2 At Nimbin the video was to be primary and there would be no printed news-sheet. To this end they intended to cable up the township to distribute the video-news to Festival participants via TV monitors strategically placed in the cafés and other gathering places of the festival.

To produce the day-to-day video news and what's-on, Glasheen, El Khouri and their colleagues were going to need a lot of equipment. They wrote a submission to the Film and TV Board (FTB) of the Australian Council for the Arts, under the banner of the AUS, and were granted $15,000 to purchase equipment for the project. They bought three 1/2" open reel (EIAJ standard) portapaks, a colour Shibaden 1/2" 'bench deck' video recorder, a small studio camera, lights, video tape, TV monitors, miles of cable and a van in which they could carry everything from Sydney to Nimbin. It was with the receipt of the funds that they decided to call themselves Bush Video.

Glasheen had a studio in the Fuetron Building in Bay St, Ultimo, where many others also interested in the Festival project gathered. With Jonny Lewis and Anne Kelly, Tom Barber, the technical wizard Jack “Fat Jack” Jacobson and others, they became an active group of artists, architects and technicians interested in the idea. John Kirk, an Australian who had been living in London since 1970 and working with the British TVX group established by John “Hoppy” Hopkins (who had also established the underground newspaper the International Times) heard about the proposed Festival late in 1972 when Johnny Allen wrote to Hoppy about it. He returned to Australia bringing with him his experience in activist video gained while with TVX, to become part of the group preparing for the Nimbin experiment.

They travelled up to Nimbin a couple of weeks ahead of the festival. Glasheen had a large geodesic dome which they set up as their domestic quarters and rented a house on the main street of Nimbin which became their centre of operations and in which they set up the equipment. Then they began to cable up the township so that video recorded during the Festival could be relayed to all the Festival participants via TV monitors strategically placed in cafés and other gathering places. A collection of TVs were modified and video distribution amplifiers in little pyramids of perspex built by the more technical of the group (Fat Jack, Jack Meyer and Karl Kruszelnicki). Stringing up the cable took far longer than expected but by the end of the actual festival week it was more or less completed and the first tapes were shown. Much of their time was spent in providing instruction and equipment to Festival participants but El Khouri managed to spend some time going out around the festival to record events, covering the Dollar Brand (aka Abdullah Ibrahim) and Bauls of Bengal's concerts, as well as general day-to-day goings on. Many of the festival participants were also recording events and although much of it was not great video, at least some was watchable.

After the Festival most of the people who had become engaged in this community video project stayed together, setting up the equipment used in Nimbin now at the Fuetron Building studio.

One of the main tasks was to edit together the material gathered at Nimbin. At this point in the development of video (mid-1973), editing J-format 1/2-inch video was very difficult. First you needed two decks, one of which should be a bench deck with an easy to punch record switch. The two decks are wired together with video and audio from the playback source connected into the input of the record VTR. The source tape and the record tape are set up on the two machines and played through to the point where the edit has to be done. Both tapes are then wound back, by hand, by the same distance - the usual trick was to mark the tapes at the sound head with a ‘chinagraph’ (wax) pencil and wind the marks back to the first tape guide post on the supply side of the machines. Both tapes were then played and as the mark went over the sound head again you pressed the record switch, and hoped that everything was okay. Consequently edits were not often good and there were lots of loss of sync events in the video. Fine production editing was not possible. However John Kirk did manage to edit a compile of Nimbin tapes and these were included in the film and video collection … over to you which was shown in London in April 1975.

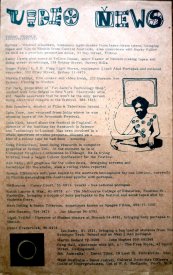

Bush Video was about medium as communications, about synthesising new realities. Several members were interested in the ‘alchemical’ or transformational potential of video while others were interested in the possibilities it offered for bringing social change and liberation to the community. Not long after the return from Nimbin they were given the opportunity to edit an issue of the UNSW students newspaper Tharunka to introduce the ideas that lay behind video. The Bush Video Tharunka 3 summed up the politico-aesthetic thinking of the experimental art world, the techno-freaks of the day, through both the recognition of the ecological linkage between the biosphere and the development of the community politically, environmentally and spiritually. Their diverse interests, ranging from the practical to the artistic to the techno-mystical, included:

-

John Kirk’s legal and management advice on how to set up access centres so as to “get together with your community to get machines, money and guarantees of access”.4

-

Considerations of the cable network experiment at Nimbin.5

-

Activist video as discussed in Tom Zubrycki's article on the use of video as an agent for change,6 Warwick Robbins' article on the Canadian “Challenge for Change” project7 or John Kirk’s article on videotapes about housing problems in London.8

-

Jonny Lewis’ article on the usefulness of Super-8 Film and Polaroid instant photography in video work.9

-

Joseph el Khouri’s discussion of the Memory Theatre: “Notes Towards an alchemy of Communication.”10

-

Mick Glasheen’s Buckminster Fuller derived “Communication as Sharing of Conscious Experience of Energy”11 which he “wrote in that year in 1967 when I finished uni and I had time to research. This was written for the World Design Science Decade … [which] was on in London in July ‘67 and … since … printed by the World Game and the International Times”,12 and this issue of Tharunka.

Others who had met them at Nimbin also became involved,13 including the electronics enthusiast Ariel. He commented:

“I’d been interested in electronics first, and then when I met the people in Bush Video I just became very interested in the whole video thing. So when I came back to Sydney I went and saw them at Glebe and I just sort of fitted right in with what they were doing, and it just didn’t seem to take that long to start picking up all the stuff involved in doing it. Obviously I was lucky I already knew about electronics.14

The interest in the electronic image and the potential it had for changing the way one saw things, and especially the use of video feedback, became a major part of the experimental process that they lived. There were regular Video Theatre evenings that involved long jams with video and electronic music as well as the general exploration of ways to develop new kinds of image generation. They tried out new synthesiser techniques, (mostly with Ariel and Fat Jack) explored computer graphics (through Doug Richardson’s PDP8 based computer graphics facility at the University of Sydney), hired a Cox Box colouriser from its distributors to produce coloured feedback and other synthetic imagery and assembled a film-to-video chain for Glasheen’s time-lapse film that he had begun gathering around Sydney in the late 1960s as well as filming in the desert in his first trip to the desert and Uluru in 1971.

Glasheen’s description of the attraction that video feedback had for him illustrates a facet of the general underlying aesthetic that guided Bush Video in much of its work

“I was drawn to the organic nature of it, … it seemed to me that video and electronic art is really an image of … energy! It's live light energy! Electromagnetic fields that are made visible! And so I was just attracted to that, [and I thought] … This is amazing! That we've got our hands on this… that we can look at... Just like ... the first time I saw a television image I couldn't believe it. You know, there's this glowing cathode tube with an image there that was alive. So I just felt that there's life there, this new life-form, that could be felt - when you're doing video effects, when you're doing feedback, the feedback effect of video, Bush Video pursued hours and hours of this feedback... Then I was feeling drawn to that because it was this kind of... it seemed to be that that's where the life was... in this machine. And what could be coaxed out of this? How could this be understood? What was this? And years and years later I kept on puzzling about what is this? What is the philosophy behind it? What is the scientific principle that's going on here? I didn't understand what it was at all. But now it seemed to come out that it’s like a Mandelbrot set, in its kind of feedback formula. Like, this simple iterative process.”15

They also explored new situations in which their video skills could be used to help the community; recording shows, teaching others about video and where possible earning a little money so that the whole project could be continued. Bush Video became a centre for much of the local experimental community, particularly the architecture and theatre scenes in Sydney. They recorded plays at the Nimrod Street Theatre. One of the early members, Martin Fabinyi along with John Kirk, produced The Vacuum, which was a TV talk-show send-up featuring Sylvia and the Synthetics, who were part of the revival of cabaret in Sydney in the 1970s. The White Company, a group of travelling players in the model of the medieval Mummers troupes, performed during some of the video theatre evenings.

The technical aspect of the very experimental work that they did at the Fuetron studio was often very unstable and not much finished video was made but there were a few important pieces. Of these MetaVideo Programming One (1974), purchased by the Philip Morris Art Grant is perhaps the most complete. It was included in the Philip Morris Art Grant exhibition Australian Art of the Last Ten Years at the NGA in 1982, and is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

El Khouri was perhaps the most interested in the transformational potential of video, making Mysterious Conjunction, which was based on the alchemical studies of Carl Jung, plus a piece based on a lecture by a visiting Hindu guru called Ajit Mookerji.

There was quite a lot of computer generated imagery, especially that based on Hindu tantric Yantras made by Ariel at Richardson’s facility. Much of the computer images were mixed into the tapes that were produced including works like I Know Nothing which also consisted in Lissajous figures and feedback all colourised with the Cox Box. It and another work of a similar nature called Escape From Reality emulated the long jams/mixdowns of the Bush Video Theatre evenings.

Money was always tight, despite support from the Arts Council, and in early 1974 Bush Video had to move out of the Fuetron building. They were fortunate enough to be invited to live in an old mansion on Oxford St, Paddington. In its backyard there was an independent school called Guriganya, which had been set up by among others Bill Lucas, a somewhat maverick architect who had taught Glasheen at UNSW. They continued their video activities, and became something like mentors for many of the kids who were students at the school. One of the more surprising results of this move was that right across the road the FTB of the Arts Council had set up City Video, the first Video Access Centre in Sydney,16 and the National Resource Centre, which was to be the hub of the nationwide network of access centres they initiated under their local version of the Canadian Challenge for Change project. This led to a great deal of interchange between both groups and later when Bush Video disintegrated some of its people took up work at City Video.

In early 1975 Bush Video was invited, through their connection with Doug Richardson and their general role in the electronic culture of the time, to participate in the Computers and Electronics in the Arts exhibition that Richardson was organising for Australia ‘75 (a Festival of the Creative Arts and Sciences), to be held in Canberra in March 1975. They drove down to Canberra, set up the dome and camped out at the Commonwealth Park site. Ariel and El Khouri set up the monitor stack and video players, as used in the Bush Video Theatre evenings, in a wall of monitors on the stage of the Ballroom of the Lakeside Hotel in Canberra, which served as the main venue for the exhibition. They more or less reproduced the video theatre set up they had used at the Fuetron building and as Ariel has said:

“At things like Australia '75 we just used what was available at the time. We had about 10 vcr's and monitors all stacked in different ways and in a darkened space you could actually see all these separate tapes running at the same time so you could get a mix, if you like, in the viewing space of all these different computer and analogue generated video sources.”17

People thought it was amazing because they had not yet seen colour TV. They showed the mixed tapes of feedback, computer graphics, synthetic and colourised video that Bush Video had used as layers in the theatre events as well as the more complete pieces.

After Australia 75 the linkages among the different members of Bush Video were gradually overcome by divergent interests and internal rivalries and Bush Video separated, never moving back into Guriganya after the trip to Canberra for Australia 75, with members going off in their different directions to follow up their separate interests.

Author: Stephen Jones

- 1. David Weston, “Videots Unite”, Nimbin Examiner, (February), 1973)

- 2. See http://www.milesago.com/festivals/wallacia.htm

- 3. Bush Video (editors), Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, Sydney: Student Representative Council, University of NSW.

- 4. John Kirk, “Macro Micro - Video feedback world interactive net.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, pp.12-3.

- 5. Transcript of “P.M.G. conference via co-axial cable Sydney to Melbourne with Bush Video and the P.M.G. Research Department”, Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, p.14.

- 6. Tom Zubrycki, “Video - Agent for Change.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, p.15.

- 7. Warwick Robbins, “Challenge for Change.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, p.16.

- 8. John Kirk, “Housing Video in London.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, pp.16-7.

- 9. Jon Lewis, “Supa 8mm and Polaroid: their relationship to Video.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, p.18.

- 10. Joseph El Khouri, “Inside a Memory Theatre: Notes towards an Alchemy of Communications.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, pp.3-5.

- 11. Michael Glasheen, “Communication as Sharing of Conscious Experience of Energy.” Bush Video Tharunka, August 7, 1973, pp.6-9.

- 12. Mick Glasheen, conversation with the author, recorded on 14 May 2005 at Palm Beach.

- 13. The author had also met them at Nimbin and joined them in April 1974.

- 14. From a conversation between Phil Connor, Greg Schiemer, Ariel and Stephen Jones, recorded at Surry Hills, 24th September 2005.

- 15. Mick Glasheen, conversation with the author, recorded on 14 May 2005 at Palm Beach.

- 16. Which later, 1976, moved to the Paddington Town Hall as the Paddington Video Access Centre.

- 17. Ariel at Synthetics, dLux Media Arts at the PowerHouse Museum, 19th July, 1998.