Tim Burns is an Australian artist who has long regarded his role as being to provoke the public into thinking about social issues. Many of his works have been controversial while showing a wry humour and a tendency towards the dangerous. He began making video while he was involved with the Yellow House in Sydney, and was also strongly interested in the political art/work expressed in the poster work and other activities of artists at the Tin Sheds. He made films with Super 8, and from 1973 produced a range of works using video. He was involved with Bush Video, although he disagreed with their view of video as a transformational/alchemic medium.

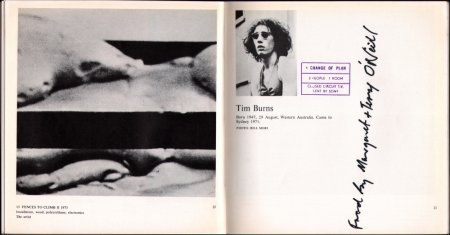

In 1973 he was invited to present a work in Frances McCarthy’s1 and Daniel Thomas’ exhibition Recent Australian Art, held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (18 October – 18 November 1973). Burns proposed a work to be called Fences to Climb II but changed his mind at the last minute and asked if he could present a new installation work, A Change of Plan, which would consist of two people in a room with closed-circuit TV (lent by Sony), and would be “a closed-circuit television piece to surprise gallery-goers into conversation with the screen.”2

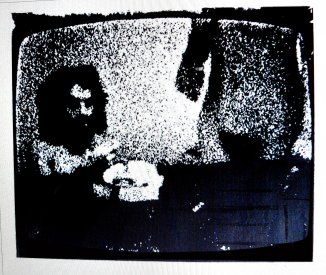

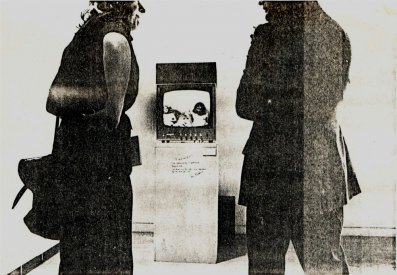

A room was built in which the two people (Barry Prothero and Ursula Maele) would spend every day under constant video surveillance for the month of the exhibition. That they were to be nude for the period was not divulged until the opening night, but Burns had warned that they might verbally abuse the audience. The audience saw a TV screen on which the two actors appeared naked. The video was relayed from the room immediately behind the screen via a portable video camera and microphone, but the audience didn’t at first know that this was the case, and as Thomas says, “It was artistically stimulating to set up confusion between broadcast or pre-recorded vision on the one hand, and realtime viewback on the other.”3

The audience was invited to speak to the actors through a microphone while viewing them on a video monitor. The actors tried to provoke a level of spoken abuse but, as the audience was not overly disturbed, Prothero took it upon himself to up the ante by walking out in to the gallery to take a toilet break, without getting dressed. This seriously disturbed the gallery attendants and the police were called, arresting him for indecent exposure, but the charges were eventually dismissed and the work was closed for only five days.

An Australian critic for Art Monthly, who used the pseudonym Gene Autry, in a recent description of the work comments that members of the audience were surprised that, upon going up to the screen, “the naked people started talking to them”. He continues:

“This was live interactive closed-circuit television and they could watch you while you watched them. They were right there inside the room-sized box in front of you. Compared with the more earnest video works of the time this performance piece was very clever and very funny. It was also a great deal more incisive than today’s reality television shows which it anticipated by almost thirty years.”4

This is perhaps the first specifically video installation work shown in Australia, and, as Thomas suggests, could be described as “Australia’s public debut of what is today called ‘new media’ art.”5

Burns has commented: “A Change of Plan was about the verbal or performance elements — the best attribute of video at the time, not withstanding that CCTV or surveillance was something people had little experience of, which set up Barry’s emergence ‘into the reality frame’. In the end video was performative and informational or documentary driven at that time for me. I was more influenced by Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy’s work where they mark the frame edges of a camera facing the wall by the one behind the camera describing the frame to the other who marks the wall with tape.”6

During this period video was seen as having a potential to bring about a considerably more accessible media, and it was out of this notion that the video access network grew in Australia. A wide group of artists and activists in Australia were interested in this more political usage of video. There seemed to be two lines of approach. One was the use of video to disturb the complacency of the viewer’s sense of the world, and the other was an engagement in and through documentation of direct political action at both the governmental/institutional level and at the community level.

Tim Burns’ approach to art and to the use of video was aligned to the former, which allowed him to become a direct provocateur for the latter. In 1974 he had video works in two shows held in quick succession at the Ewing Gallery at the University of Melbourne. In the first, one of Ewing Gallery’s ‘ideas shows’, Boxes, and billed as “Responses of some Australian artists to a basic object, a cardboard box 13x11” (July – August 1974), Burns returned the cardboard box, now labelled The Philosophy of Video and “filled with a two-part resin at the centre of which was a cavity containing a video of the artist mixing and pouring the resin.”7 7 In the second show, Events/Structures (September – October 1974) Burns’ installation, For the Sake of Art, comprising several TV sets that show a videotape (originally shot on 35mm film with a slow-motion camera) demonstrating the ICI Explosive Users Guide in which the example is the very TV sets on which the tape is being shown.

Of this video installation/performance Burns notes: “With For the Sake of Art … David Perry shot the video that appeared on the screen in the finished work on a road in Chippendale, where I drew on the road the construction of the device and the TV. Although this was not overly telegraphed to the audience with a count down at the end from 10 to zero when I would fire an electric detonator and the TV would blow, thus revealing the subject and object of the drawing. The tests were shot on 35mm [or 16mm] in Western Australia by John Clarke to test the placing and amount of explosive to be used. This footage was later used as the indicator of the trigger for the exploding videotape in the end of Against the Grain. Donald Brook allowed another showing against the wishes of his department at Flinders Univeristy, where I was artist in residence in 1975.”8

- 1. (now Frances Lindsay)

- 2. “Museum pieces: 3D TV, 1973”, Daniel Thomas, Art and Australia, Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 2004, pp. 550–551.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. “Big Brother is Ignoring You”, Gene Autry, Art Monthly, No. 140, June 2001.

- 5. Thomas, op cit.

- 6. Tim Burns, email to Stephen Jones, 6 October 2009.

- 7. “Arts Melbourne and the end of the seventies”, Meredith Rogers, in Helen Vivian (ed.), When You Think About Art: The Ewing and George Paton Galleries 1971–2008, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 44.

- 8. Tim Burns, email to Stephen Jones, 6 October 2009.

![Photograph of the aftermath of For the Sake of Art at the Ewing and George Paton Gallery for their Event Structures exhibition, 1974. According to Burns, the people in the lower shot are [from left] Peter Timms, Alex Danko, Mitch Johnson and Meridith Rodg](../sites/default/files/imagecache/mediaviewer/Burns_For-the-Sake-of-Art_Ewing_74_pvw.jpg)

![Photograph of the aftermath of For the Sake of Art at the Ewing and George Paton Gallery for their Event Structures exhibition, 1974. According to Burns, the people in the lower shot are [from left] Peter Timms, Alex Danko, Mitch Johnson and Meridith Rodg Photograph of the aftermath of For the Sake of Art at the Ewing and George Paton Gallery for their Event Structures exhibition, 1974. According to Burns, the people in the lower shot are [from left] Peter Timms, Alex Danko, Mitch Johnson and Meridith Rodg](../sites/default/files/imagecache/Medium/Burns_For-the-Sake-of-Art_Ewing_74_pvw.jpg)