You don't tend to find too many women working in high technology. I've been very lonely. As Jan Zimmerman1 puts it, “In the modern world where science and technology have displaced the gods of rain and wisdom, men still constitute most of the high priests worshipping at the laboratory altar". Why is this?

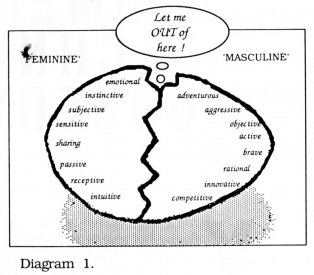

In what some call the post-feminist era - as if feminist concerns have been fully addressed and corrected! - we still find rather rigid definitions of what constitutes masculine and feminine behaviour. Diagram 1 shows a representation of this.

There is still a lot of subtle and not-so-subtle pressure on both sexes to limit themselves to traits traditionally associated with their gender. Men are socialised to develop their 'masculine' aspect and to suppress (and hence despise and fear) their 'feminine' aspect. Likewise, women are restricted to the 'feminine' and discouraged from being ‘unladylike'.

You can't help noticing the overlap of the 'masculine' qualities with those usually associated with science and technology. Also striking is the overlap between the 'feminine' and the arts.

Despite the fact that they are no longer barred from entering, girls definitely get the message that science and technology is for boys or for the occasional, exceptional girl. This is reinforced in many different ways. We have to ask how many girls have been lost to science and technology through lack of support, encouragement, desirable role models or even decent teaching.

The recent case of sexual discrimination brought by 15 year old Melinda Leves before the NSW Equal Opportunity Tribunal highlights the often poor technical education available to girls. She was offered textile design and home science while her twin brother chose from technics, electronics, computer studies, motor mechanics, woodwork, metalwork and plastics. The twin's mother said of Melinda, "She's losing confidence in herself, her self-esteem is dropping. The difference between the two kids who were academically identical is remarkable.”2

I ask myself how I managed to become and survive as A Woman In High Technology. Since we now know that girls learn better in a single sex environment (while interestingly boys do worse) it's probably no coincidence that I attended an all-girl's school. Popularity with boys was very important to me then and I doubt I would have risked being called 'un-feminine'.

I do recall that the maths and science education offered me was of an appalling standard but because I enjoyed the work and was encouraged by my family, I supplemented it by teaching myself out of text books.

Being successful, I was directed towards studying sciences at University (since it had higher status) and away from the arts. Not being able to draw realistically seemed to prove the validity of this direction. I recall science teaching and medicine as being the only career choices offered to me. And I've never forgotten my surgeon father (whose frantic on-call life I had no desire to emulate) telling me that medicine was a bad choice for women because it blunts the emotions.

Later at University I lost a lot of confidence and drifted towards the biological sciences which seemed friendlier to women. I became a biochemist. Five years later I realised my mistake and retrained as a computer systems analyst. I moved into a world of high technology and was exhilarated by the technical side of computing.

However I felt very confused about whether being a computer scientist made me a 'non-feminine' woman. Especially as I needed to suppress despised 'feminine' qualities (e.g. emotions) at work if they could be seen as making me seem not ‘as good as a man'. I had to be aggressive, competitive and sometimes insensitive. The dominant mode was clearly 'masculine'. To be treated like 'one of the boys' can be brutal and I was untrained at this. I felt isolated being often the only woman (and sticking out like a sore thumb) at meetings and seminars. Luckily I had no interest in having children for if I wanted them I knew I would have been seen as not 'serious'.

I think in some strange way I sometimes pretended I was a man. Well a boy, I suppose. I hated to have curves. Of course I fooled no one. And to my shame, I allowed myself to feel superior to other women because I was "making it in a man's world". I looked down on the 'feminine' in myself and others.

Unsurprisingly (to me now anyway) I felt a lot of frustration and self-hate. I began seeing a psychotherapist to try to soft things out. I began to rediscover my creative side, long dormant since primary school.

After a long battle to re-gain my confidence in my creativity, life became a search for a reconciliation of both technical and creative interests in my work. Around the same time, sophisticated computer graphics began to be developed. At last! Having the necessary computer skills I could use the early 3-D animation systems and because I had some artistic skills by now, I became a 3-D animator. I became very excited (and still am) about how computers could facilitate new kinds of an and expressivity.

The systems I used became more user-friendly. The required computer skills diminished slightly and the aesthetic became more important, particularly in the United States.

The strange thing is that I began to be considered an artist and not a computer scientist. The awful thing is that I caught myself believing it too and feeling less confident about the technology. I made an effort to learn the new programming languages and concepts, and am now designing and programming a computer graphics system.

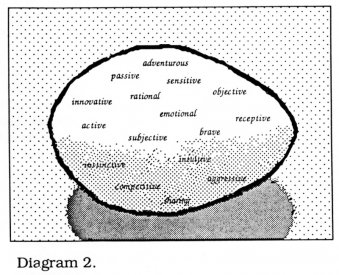

Obviously I am still working on reconciling my 'masculine' and 'feminine' interests. It's still a hard thing to manage in the workplace today. But I think it is crucial, not only for me or for other women or for men but for science, technology and society as a whole. I reject utterly a view that forces men to be 'masculine' and that forces women to stay within the 'feminine'. To live fully we must integrate and value both these aspects. See diagram 2.

As Marion Woodman3 puts it, "We are so busy doing and achieving that we have lost touch with our inner life, that life that gives meaning to symbols and conversely the symbols that give meaning to life. No other era has so totally divorced outer reality from inner reality, the matrix of which is the Great Mother. Never before have we been so cut oft from the wisdom of nature and the wisdom of our instincts."

Science and technology need greatly increased participation by women and must start to respect and accord equal value to the 'feminine' aspect. We need to assess who benefits from the exciting advances in these areas and who controls them. We need to make sure that men, women, children and our environment itself will benefit from these 'advances'. We need to realise the power to define reality that will accompany such things as computer data bases and the simulation of realistic images - not to mention the exotic weapons of destruction: neutron bombs, blinding laser beams, killer satellites now completely under male control. We need new ways of defining power, to change from power-over-others to power-from-within.

I realise this is easier said than done. There's a lot of vested interests in keeping things the way they are. However I feel encouraged by recent developments in science education for girls, in the questioning of technology's progress for progress' sake and in the environmental and nuclear disarmament movements. Science and technology desperately need the influence of the 'feminine' if they are to be of real long-term use to humanity. The exciting possibilities of computer-mediated art will be useless to me when a nuclear bomb destroys the circuit boards along with most everything else.

I'd like to conclude with an interesting excerpt from an essay by Sally Miller Gearhart4. Having talked about the myth of combining a 'feminine' and 'masculine' partner in a heterosexual union to make one 'whole' person (hence Mr. and Mrs. John Smith!) and the myth of male superiority, she writes “Through the perpetuation of these myths, society's misogyny becomes increasingly the norm, apparent not only in sexist jokes but in every woman's second-rate social and economic status, her obliteration from history, her media image, her own depleted self-image, the way she laughs, the clothes she wears, the thoughts she thinks - or fails to think, the way she walks – or fails to walk, the words she says - or fails to say, the jobs she has - or fails to have, the job she wants - or fails to want. Of that societal disdain each woman has drunk so deeply that a hatred of herself as woman poisons her every thought and action; she becomes her own worst enemy, believing she doesn't want to do self-fulfilling things (like science and technology) because she believes she can't do them because she's been so deeply programmed to believe she shouldn't do them. With that societal disdain she has sprinkled her separate prison of isolation and has secured herself from all others; further this societal disdain of women has steadily fed the fires of competitiveness and corporate capitalism until only now does a woman realise the extent of her complicity and that of other women in the whole planet's pell-mell race to annihilation."

1Jan Zimmerman, Once upon the Future: A Woman's Guide to Tomorrow's Technology, (London: Pandora Press, 1986).

2"Setting The Classroom to Rights", The Australian Women's Weekly, June, 1986.

3Marion Woodman, Addiction to Perfection: The Still Unravished Bride, (Toronto: Inner City Books, 1982).

4Sally Miller Gearhart, "Gay Civil Rights and the Roots of Oppression”, in Gayspeak, ed. James Chesebro, Pilgrim Press, 1981.