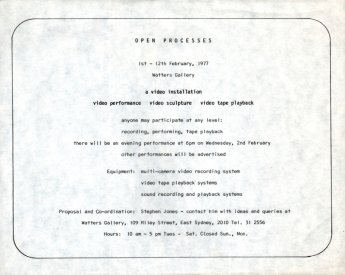

"Open Processes": report in City Video, vol.1, no.3.

Proposal: To provide an environment at Watters Gallery, Sydney, in the last two weeks of January, for experimenting with the space and installation, and then February 1-12. as a space for working, in public ways, with games, performance, playback, videotaping, realtime audio/video synthesis activities, theatre. dance, music, hardware installations (Video sculpture).

A process environment containing a supply of video hardware, set up in particular configurations. Each element of the system is capable of being coupled to a variety of other elements of the system following the syntactical rules of video and the configurations generated by ourselves/minds and our interactions.

With the above proposal and its accompanying text people from video centres, music departments, art schools and so on were invited to participate in the Open Processes show.

I threw a very wide net for all kinds of input to the show. We got video tapes, performances and installation set-ups for software and hardware. Using as loose a structure as possible the show took shape according to the input available from people who got involved.

The idea originally developed in March 1976 in conversation with Frank Watters of the Watters Gallery. At that time I had no idea what form the show would finally take. Over the next few months I tossed around a series of ideas while working with video in many areas; in the production of my own tapes, in video dance work, in real-time concert recordings, teaching video practice and looking into such things as electronic music and sound and image processing devices, and multi-media performance activities.

Of course, this is an idealisation of intention and I don't consider that I was entirely successful in accommodating the full range of input and experimentation that would have developed if this intention had been fully realised. Nevertheless, a large number of people spent a good deal of time working on the show and a fair range of flexibility in situation and system was achieved allowing a considerable amount of software to be generated and displayed in a generally satisfactory way.

I applied for a grant for financial support for the exhibition, and its development, from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council. I received $2,000 of the $3,500 budgeted, but this was plenty to get moving on. I later received another $500 from the Creative Development Branch of the Films Commission, which pulled the financial situation back into reality. Ultimately the show cost the $3,500 budgeted, but I probably couldn't prove that to an auditor.

Having received the VAB grant, I decided that the form of the show would be built up from real-time performance videorecordings as the major activity, in that most of the response was coming from people in performance mediums such as music and dance. There was also, in various centres, a great deal of videotape already available, most of which hadn't received much exposure. The major sources of videoprogramming in Australia are the Video Access Centres; with a variety of individual's work being in the VAC's libraries or with the videotapemakers themselves - people such as Joseph EI Khourrey, Ariel, Michael Nicholson, Dave E. Perry, Clive Scollay and Paul Frame.

It became apparent that video could by no means be touted as a one man show situation, which is what usually develops in the commercial gallery situation. Video activity necessitates a great deal of co-operative activity between a very wide range of people and it seemed that the solution to the problem of how to do the show was to let it do itself. That is, I would make the proposals and organise the financing of the show; gather the equipment and, most importantly, invite as many people as I could to become involved in the show. Thus it would be these people who would make the show.

While these show the production,and display ends of the video process there is still a very important aspect: the video space itself with its concepts of feedback and simultaneity; to be exposed. This, perhaps, can be described as video sculpture. This type of work is charged by the problem of bringing into a person's consciousness the relationship of the image, one's own or some other, to the video system, e.g. the facility to look at one's back and one's front simultaneously. This extends to the facility to examine all one's social interactions, one's image, presentation and responses and all one's immediate social relations; playing with video feedback at all levels, electronic and social. These kinds of problems require a system where the process is exposed and easily controllable, developing the time, process and personal operational elements into some kind of video environment. This, unfortunately, was the most weakly developed aspect of the show, despite its importance.

So the task became an information-invitation to all kinds of people to come in on the show; and assembly of enough equipment to do all the things that people might have in mind.

Paddington Video Resources Centre agreed to loan us b&w VTR's and monitors, lights, U-matic VCR's and a good deal of the colour production gear. CCTV loaned us the Fairlight coloriser which we used to colorise monochrome video from the b&w production system hired from Warwick Robbins. We hired 12 colour UHF receivers from Radio Rentals, and a couple of U-matic cassette players and monitors from Western Access. The Arts Council of NSW lent us half a dozen b&w monitors, a camera and a VTR. Finally, the Bush Video equipment and some of my own, bought second-hand, were used in experimental set ups and for video sculpture.

I published the proposal containing various statements regarding the ways in which the show could run and inviting participation, interspersed with photocopied video photographs. With this in hand I then approached various people and we talked of the possibilities. Most of the people who received the proposal participated in some way. Proposals were also posted to various video and media centres and galleries in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane. Participation came in many forms - besides the people performing within the videorecording situation. Pieces included:

1. "He, She & Me", by Bob Weis and Judi Stack of the MAVAM Co-op, Melbourne, produced a multi-track video-tape presentation piece which, ideally could be switched through an array of monitors by the people watching. Content of the tape was drawn from broadcast TV and other sources and formed a visual dialogue between the inane violence and sexism of TV content and the reality of daily and sexual life. A very effective confrontation of image, myth and reality for the viewer.

2. "Time to Move On, The Sugar is Running Out", by Paul Frame and Clive Scollay with help from Martin Wesley-Smith and Ariel produced a multi-track realtime mixdown of prepared tapes, sound track, live music, live video, dance to bring about an information media environment that made me feel as though I was going through a war.

3. Jacqui Caroll and Jilba Wallace produced several dance/theatre pieces incorporating live and video-taped action and using the potential of the gallery spaces effectively.

4. Steve Dunstan, using his CUBE digital music synthesiser, as well as supplying music for many situations (as did a lot of other people working in the show) set up a dance piece for Brigitte Murphy and Janie Douglas, using video-keying to place the dancers into a painting of his as set for their dance.

5. Geoff Tenant sent several sets of drawings for videosculptural/environmental works which, unfortunately were not executed.

6. Fat Jack documented the show in photo graphs using an ancient 4 X 5 plate camera and an on the spot processing system.

The primary function of the show developed as the live recording situation with real-time display of all levels of video input/output. The ground floor of Watters was converted to a studio space into which we placed b&w cameras (4) (Sony 3250), 3 with viewfinders on tripods, 2 with dollys. The 4 Cameras were cabled to a vision mixer (Sony SEG2 CE) and looped through to input monitors. The SEG was externally driven. The output from this mixer went to a b&w ½” VTR (Sony 3670), line output monitors in monitor stacks in the performing space and the front section of the gallery. The mixed b&w output was also sent to a coloriser (Fairlight model 108). This colorised video, RGB, was then encoded (in a Fairlight model 106 PAL Encoder) and mixed with output from a colour camera (Sony DXC5000) in a colour mixer (Sony SEG2000) and recorded on U-matic VCR (Sony 1810) and displayed on colour monitors throughout the gallery. The whole system was locked together and driven by an Aston colour sync pulse generator and a Sony pulse distribution amp. We also used an Advent Videobeam video projector. Sound was mixed through an 8 channel mixer and recorded, in stereo, directly onto the video cassettes.

Thus we had a wide range of possibilities in terms of image mixing and the system was used to it's full extent over the whole period as a performance recording and display facility with solid real-time control over all parameters of the. image mixing - but it didn't help to be interrupted during a mixdown. The state of mind of being totally expanded to the ends of the cameras, selecting and mixing images as they arrive in real-time process (a feeling that I imagine to be similar to the feeling of surfing a wave) determined by the feedback from the line output monitor as visual image-control is for me the most important direct experience of video production unfortunately not an experience that everyone can share at once.

In the viewing lounge we provided a couple of U-matic cassette players and a range of tape selected from here and overseas. The VCR's were played into a bank of colour UHF receivers with each VCR tuned to a different UHF channel so that the viewer could select either of the two sources in the lounge as well as the output from the performance recording by switching channels on the receivers. The viewing lounge was remarkably well used, people watching often for hours on end. As one person said, they saw "a thousand paintings that had never been painted in five minutes of watching the screen".

And so, what were people's responses? For the people who got involved they couldn't have gotten deeper into it. Crews were all scratch, i.e. put together from whoever was available in the gallery at the time, so lots of people got a good chance to work within the studio framework as camera operators, vision mixers, sound mixers, etc. Obviously the quality of the production is not up to broadcast standards, but, when you see the tape you realise that all that professionalism guff is generally a load of rubbish, because the programmes are very watchable. People who chanced to wander in, if they didn't know anything about video, it seems were, unfortunately, very alienated by the technological tour-de-force of masses of hardware.

This was a bad failure of the show in that we were unable to provide the kind of personal and conceptual back-up necessary to help these people into an understanding of what was going on. Most performances were reasonably well attended and I did find that quite a few people came by whom I didn't even see, despite spending almost all my time in the gallery. Of course, the critics ignored the thing completely, but what could you expect.

Basically the show was very successful: a number of people had the opportunity to work in a studio context who had not even touched video before; a fair number of Performing people were videotaped, and a heck of a lot of people watched a heck of a lot of videotape from all sources. The task now is to get the videoprogrammes from the show exposed as widely as possible. They are for sale from myself (with about a third of all sales going directly to the performers) and for hire from the Sydney Film-Makers Coop or the Paddington Video Resources Centre, Sydney.

Here is a listing of all programmes presently available from the show. All are in colour and on 3/4" U-matic cassette.

001 Video Music Improvisations (60 min.)

Acoustic and electric music by various people improvised during a number of sessions throughout the show with:

Steve Dunstan – synthesisers, bass, mandolin, etc.

Delta Ray - guitar, keyboard synthesisers.

Nicolas Lyon - Bass, violin, kalimba.

Joseph E1 Khourrey – keyboard synthesisers.

002 Electrons (60 min.)

Electronic music by Steve Dunstan on CUBE digital music synthesiser and the EMS Sythi AKS, with video feedback effects.

003 Greg Schiemer (20 min.)

Playing banjo tuned to a raga tuning.

Colin Offord (40 min.)

Songs for flute - pieces for various flutes and percussion.

004 Level Four (60 min.)

Improvised music for synthesisers.

Ian Fredericks - percussion

Jane Fitch - vibes, marimba.

David Hush - Fender Rhodes piano.

Mark Underwood - flute.

005 River Ballet Impressions (60 min.)

Two dance pieces by Brigitte Murphy and Janie Douglas. The first to setting and music by Steve Dunstan, and the second to a setting by Warwick Robbins and music by Steve Dunstan and Nicolas Lyon.

006 Flying Fish (40min.)

Light acoustic folk music with:

Neil Pike - guitar.

007 Suta Music (15 min.)

Songs and poems by Terry MacArthur, performed by:

Alan Japal Jari - guitar, vocals.

Duncan Sweeney - guitar, vocals.

Terry MacArthur - lyrics.

008 Dance Works (60 min.)

(a) Merrilee Macourt - choreography.

Eleanor Brickhill, Judith - dancers.

Steve Dunstan - sound.

(b) Jacqui Carol - concept and dance.

Carl Vine, Anthea - music.

(c) Russell Dumas - concept and dance.

a composite of dance works performed during the show.

All works recorded live at Watters Gallery, Sydney

February 1-12, 1977.

Production: Stephen Jones.

Production assistance:

Warwick Robbins

Rodney Aeon

Delta Ray

Paul Frame

Richard Smith

Margot Oliver

Stephen Jones 49 William Edward Street, Longueville, NSW.

An explanation of the System in the gallery

[See image called Main Production System] The Four Monochrome Cameras are mixed on the monochrome SEG (Special Effects Generator), from there one output is fed to a monochrome VTR (AV3670CE), and the other output is fed to a six stage Fairlight Coloriser. (This enables one to assign a specific Color to a specific tone of Grey, Black or White). At the head of the system is a Sync Pulse Generator,which in turn is fed to :

1/ The Monochrome SEG

2/ A PAL Color Encoder

3/ The Color SEG

4/ The Color Camera Control Unit(CCU)

The PAL Encoder takes the Signal from the Fairlight Coloriser, Encodes the signal,and passes it on to the Color SEG.

A Phase Shifter is connected to the Pulse Distribution Amplifier, this enables the Chroma and Burst Phase to be corrected before it is fed into the System.

The Color Camera is Color Corrected at the CCU, then is fed to the Color SEG. The Color SEG receives Composite Color Signals from the monochrome SEG via the Fairlight Coloriser, and the Color Camera via the CCU. These two signals are mixed at the Color SEG and are fed with associated audio to a U-Matic VCR, then to a Color Line Monitor.

![Cover of City Video, vol.1, no.3, with Stephen Jones in front of monitors at Open Processes [photo: Sandy Edwards]](../sites/default/files/imagecache/mediaviewer/city_video_vol1_no3_sj_on_cover_800h.jpg)

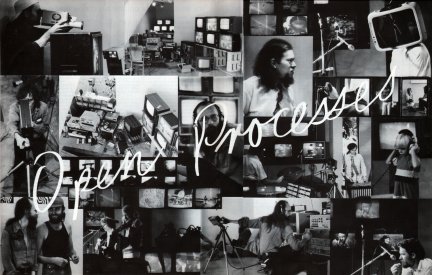

![Open Processes: Main production system. [Drawing: S Jones]](../sites/default/files/imagecache/mediaviewer/main_production_system_sj.jpg)

![Cover of City Video, vol.1, no.3, with Stephen Jones in front of monitors at Open Processes [photo: Sandy Edwards] Cover of City Video, vol.1, no.3, with Stephen Jones in front of monitors at Open Processes [photo: Sandy Edwards]](../sites/default/files/imagecache/Medium/city_video_vol1_no3_sj_on_cover_800h.jpg)

![Open Processes: Main production system. [Drawing: S Jones] Open Processes: Main production system. [Drawing: S Jones]](../sites/default/files/imagecache/Medium/main_production_system_sj.jpg)