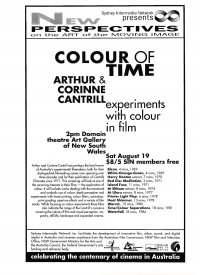

Arthur & Corinne Cantrill: experiments with colour in film.

This screening looked at one of the recurring interests in Arthur and Corinne Cantrill's films - the exploration of colour.

Domain Theatre, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Introduction:

Throughout over a quarter of a century of work, the concerns and films of Australian filmmakers Arthur and Corinne Catrill have remained consistent ... Their concerns converge around experience, both their own and that of the spectator, as they relentlessly explore the subjective experience of perception, proces and time. Their practice is firmly rooted in the body, the material. Theirs truly could be said to be a cinema of the body. The colour separation films, the image analysis films, the landscape films, the multi-screen and film/performance works, all reflect a lived body. Theirs is not a cinema of the mind. It is a cinema to be experienced.

- Barry Kapke, Cinematograph Vol 3, San Francisco, 1988.

Insisting that the Cantrill's cinema is one to be experienced is doubly important to this selected screeing. Firstly it-particularly the earlier films from the 1960s and 1970s. And secondlyto warn us that while these films have been selected aroun the theme of the use of colour in film, does not necessarily define their purpose.

In fact, when I suggested the theme of colour to the Catrills it was because I saw that the use of colour had been an issue, recurring in different ways, throughout their extensive career and so offered the possibility to present many aspects of their filmmaking. These films should be approached with attention to the delightful potentials that colour offers and how these interact across a broad spectrum of visual thought/practice. For the Catrills, these concerns encompass the nature of film ad visual perception; the emotional and symoblic use of colour; depth perception; an interrogation of traditional forms such as religious icons, still life and landscape; experimentation with laboratory processes-hand printing, print grading; aperture effects and working with different print stocks. This list could certainly be extended but is enough to signal the possible range of interest that could be brought to the appreciation of these films.

I would like to thank Arthur and Corinne for their care in selecting these films and preparing the film notes. Further informartion, particularly on their early film work can be found in the exhibition catalogue Mid-Stream published by the Ewing and George Paton Galleries, Melbourne University, in 1979.

Brian Doherty, Coordinator, Sydney Intermedia Network (SIN)

Film Program:

Eikon, 4 min, 1969

White-Orange-Green, 4 mins, 1969

Harry Hooton extract, 7 mins, 1970

Island Fuse, 11 mins, 1971

At Eltham extract, 8 mins, 1974

At Uluru extract, 8 mins, 1977

Printer Light Play, 6 mins, 1978

Heat Shimmer, 13 mins, 3-colour separation, silent, 1978

Warrah, 15 mins, 3-colour separation, 1980

Time/Colour Separation, 18 mins, 3-colour separation, silent, 1981

Waterfall, 18 mins, 3-colour separation, 1984

Film Notes:

Film, being a temporal visual art, offers a rich scope for considering the relationship of time and colour. This may simply occur with an unhurried colour shift as the moving sun alters its colour temperature through a day of filming, or it may involve a direct manipulation of the film colour through colour filters in the camera, or on the lights, or in printing.

Colour can develop in a time-frame, as music does. The colour composition in White-Orange-Green and in the side panels of Eikon, and the colour shifts in Waterfall are attempts to work with colour this way. There is another similarity to music: wavelength structures are common to colour and sound (red and low pitch sound: long wavelength; blue and high pitch: short).

From the rich blacks, whites and greys of the early nitrate prints, film emulsions have always had their own characteristic colour, by which periods of cinema can often be recognised. In avant-garde practice filmmakers have been open to the colour possibilites of different film materials, and, beginning with the pioneer three-colour separation colour work of Askar Fischinger and Len Lye, have often used them in ways the manufacturers did not intend. In some films e have shot on colour negative print stock (as in At Uluru) and used black and white negative for three-colour separation purposes.

For the first ten years our filmmaking was almost entirely in black and white (the exceptions were our art documentaries of the 1960s). With Eikon, White-Orange-Green and Harry Hooten we immediately beagn working with higly coloured imagery, often with multiple superimposition. The films up to the mid 1970s were shot on the now non-existent Ektachroe Commercial reversal stock and printed on Kodachrome, yielding a richly saturated colour.

EIKON, 4 mins, 1969

Eikon is a secular film 'icon' in which the golden colour of the contemplative central figure (a one-take shot) is juxtaposed with artificially coloured side panels of earthly activity, as in the old orthodox church icons. The 'real' time of the central image is contrasted with the fragmented and superimposed time of the side panels. The piece was realised in one gesture on a roll of film with no editing, by matting in-camera and winding the film back to add the two panels. The sound of a looped soprano note and improvised violin connect with the centre and side images.

WHITE-ORANGE-GREEN, 4 mins, 1969

White-Orange-Green is a 'still'-life with chromatic variations where the play of white, orange anad green light disrupts the illusion of three-dimensionality. The film starst with a lengthy uncoloured (white) shot of the composition to invite contemplation of the passage of time through film, after which a play of the three colours develops. The still composition allows attention to be given to the nature of filmic time and other visual properties of film, while the temporal aspect is underlined by the sound of a projector showing the workprint of the film: the splices clattering through the gate,

In our 'Expanded Cinema' shows [beginning in 1970] we extended the idea by projecting this film next to a slide of the composition and also next to the actual 'profilmic' object. We later returned to the notion of 'still-life-' in the three colour separation studies [from 1976].

HARRY HOOTON, 83 mins, 1970

The 7 minute extract from Harry Hooton illustrates a contention of this Sydey poet and philosopher who influenced us so greatly in the 1950s: 'Art is the communication of emotion to mtter' (heard earlier in the film). Black and white images shown earlier in the film are contact-printed by hand in 3-foot lengths onto colour stock, superimposed and illuminated by coloured light. Unmediated by lens optics, the colours have an unsual purity.

ISLAND FUSE, 11 mins, 1971

After the highly coloured work of 1969 and 1970 we moved towards a more austere use of colour with Island Fuse. Black and white footage shot ten years earlier on Stradbroke Island is reqorked in colour monochromes, using a technique of refilming a rear-projeted image.

The life of the landscape is thus revealed by photo-chemical means. This includes the use of superimposed and coloured negative nd positive which separate, giving an illusion of movement to the still forest... The Cantrills' intention is not just to produce a beautiful image - there is a philosophical statement about time.

- Takashi Nakajima, Image Forum No. 40, Jan. 1984 (translation: Takao Nakazawa)

The central part of the film concerns movement and gesture analysis of an archetypal Australian male figure in the landscape, repeating a scap of movement in various ways, including a highly enlarged detail of the original frame.

Island Fuse is a process piece concerned with the interaction of the elements involved in making the film: the rear-projection screen; the camera and its mechanism; the filters; the projector and its mechanisms; the film strip and frames, and the question of profilmic time as against time consumed in production of the image.

AT ELTHAM, 24 mins, 1974

An 8-minute extract from At Eltham shows the effect on the light, colour and definition of a landscape (a river seen through eucalypts) by manually 'playing' the mechanical functions of the Bolex camera: the fade mechanism, the focus and the lens aperture. The bellbirds are just as they were recorded that day.

AT ULURU, 80 mins, 1977

An 8-minute extract from At Uluru inwhich the timelessness of the monolith is suggested by negative colour, the result of using fine-grain Eastmancolour print stock in the camera, a slow speed material which reauired the intense Central Australian light for adequate exposure. A half-speed recording of the local bird call and insects contributes to the sense of cross eras. Human perception of time, colour and sound is questioned. As Einstein said: 'The distinction between past, present and future is only an illusion, even if a stubborn one.'

PRINTER LIGHT PLAY, 6 mins, 1978

Printer Light Play demystifies an arcane film laboratory practice: the grading of the colour print by adding or subtracting degrees of red, green or blue light in the printer. A male version of the 'Kodak lady' (which is ofrten spliced into leaders as a lab quality check) is subjected to a range of 84 different combinations of printer light settings out of a possible 132,651 combinations of red, green and blue. The combinations move between the lab's standard printer lights, through small variations to extreme distortions of colour balance, random combinations, and progressive colour alternations.

THE THREE-COLOUR SEPARATION FILMS

In 1976 we began a eries of 3-colour separation films which reproduce, in a technically simplified form, the principles of the early Gasparcolour and Technicolour 3-colour processes. The motivation for this work came from a visit to the Eastman house Museum of Photography in Rochester in 1974 where we were impressed by the display of early systems of colour photography and film. We wanted to go back to these early experiments and exaamine them for ourselves, using the materials and equipment avilable to us. This necessitated exposing the separations consecutively (rather than simultaneously as in the Technicolour) system) automatically introducing the element of time into our images. A one-minute study can take up to five minutes to film - changingi the filters and F-stops.

The first 3-colour films were shot in Central Australia in 1976: landscape studies. The result was close to that of reversal mateirals: reproducing the rich ochres of the desert with strong, saturdated colour. We soon noticed that elemtns of the scene moving in time (principally moving clouds in the first studies.) appeared in displaced primary colours, depending on which separation they were shot, while immutable parts of the scene were rendered in comparatively 'natural' colour. movement and time are expressed in terms of colour, and human perception of past/present/future is questioned once again: three 'presents' are superimposed in these studies.

As well, a marked illusion of three-dimensionality was often apparent - possibly due to the sharpness, and the tendency for a slight vibration to ocur around the edge of objects (which may correspond to a similar vibration about objects which is a result of binocular vision in the constantly moving, 'hand-held' human head).

We imagined we would exhaust our interest in the process after two or three films, but new possibilites continued to emerge, and we eventually made about fifteen 3-colour separation films over the following ten years.

HEAT SHIMMER, 13 mins, 3-colour separation, silent, 1978

Heat Shimmer was shot during a summer trip to Central Australia (1977-78). We appraoched a most elusive phenomenon: the shimmer caused by rising hot air in variably refracting the light which reflects form the desert landscape. Light in movement often is the only activity in the scene. The studies have differing degrees of shimmer - sometimes barely discernible, but in the final group of studes, 'Near Pimba', the shimmer is powerful enough to cause a marked separation of the three colours in the zone of air movement.

WARRAH. 15 mins, 3-colour separation, 1980

Warrah is filmed in similar country as was Bouddi, ten years earlier: the Hawkesbury River region. The complexity of the coastal bush ecology is suggested through the 3-colour separation system of filming - the patterned Angophora trunks, the folige, and paterns of shadows, water, colour, reflections in the rock pools. The sound track is a recording of choruses of kookaburras calling to one another up and down the valley, echoing the layers of film images.

...It is a genuinely successful experiment, where monetary shifts in time are registed in colour...'Warrah' is that rarest of combinations: a thinf of beauty and a treatise on form. - John Flaus, The Age, 24 February 1984

TIME/COLOUR SEPARATIONS, 18 mins, 3-colour separation, silent, 1981

Time/Colour Separations is in two parts: 'The Water Trick' and 'The Colour Illusion'. In the first an essentially colourless still life - a glass jug of water and four glasses on a white tablecloth, with a black background, is made to yield a complexity of colour by confining actions of pouring water in the glasses to specific separations. The viewer becomes involved in a kind of game in which the action has to be interpreted from the clues given by the colour.

In 'The Colour Illusion' we deal with the primary colour in light: Red, Green and Blue (and their complementaries, Cyan, Magenta anad Yellow) and primaries in pigment: Red, Blue and Yellow. The film 'plays' with the colours of light and pigment, and the moving colours on the palette and in the film emulsion. (The mixing of pigments of specific colours is affected by the layer of film on which they are mixed.) The film ends with a series of colour shifts caused by a controlled re-arrangement of the black and white separations on the three printing rolls.

WATERFALL, 18 mins 3-colour separation, sound, 1984

Waterfall begins with the notion that in certain 19th century landscape photography - particularly that of Edweard Muybridge - images of waterfalls were studes in time. The slow shutter speed ensured that the photograph did not record the water, but its passage in time, or more accurately, the volume of space it occupied during the exposure.

In this 3-colour separation film the htree superimposed images of the moving water combine into a solid, white undifferentiated volume, surrounded by coloured activity due to the variations in the flow patterns. To enhance the effect we slowed the shutter speed to about one second exposure per frame; the water becomes a vaguely delineated rush of material which appears to be rising as much as falling.

The surrounding landscape is sometimes suffused with washes of colour caused by cloud shadows moving across it during the five minutes or so required to fo the separations. This evokes early attempts at colour photography an the results of tinting and toning. Colour expands and contracts around the masses of water as the focus is adjusted separately on the three layers of film.

The soundtrack is a mux of three different waterfall effects, variously modified by a graphic equaliser, with slow changes in the frequency spectrum, anticipating changes in the image. It was composed in one take, in real time, to the film. Filming was done at MacKenzie's Waterfall, in The Grampians, Western Victoria.

... Movement and stillness, the transformations of sunlight and cloud, the features of a film that animates and performs still photography. The Cantrills' ingenious collaboration with the photographic with the photographic inheritance remains a major distinction of their work. - Kris Hemensley, Photofile Vol. 2 No. 2, 1984